Calculate the capacity of the die casting chamber

Calculating the die-casting chamber capacity is a crucial preparatory step before die-casting production. Its purpose is to ensure the chamber can accommodate the volume of molten metal required for each die-casting session, while avoiding the negative impact of excessive or insufficient capacity on production. If the chamber capacity is too small, insufficient molten metal will result in under-casting and cold shuts. If the chamber capacity is too large, excess molten metal will remain in the chamber for extended periods, where it will oxidize and form scale, affecting casting quality while increasing metal and energy consumption. Therefore, accurately calculating chamber capacity requires a consideration of casting quality, gate system volume, and process margins, and is crucial for ensuring a stable die-casting process and reducing production costs.

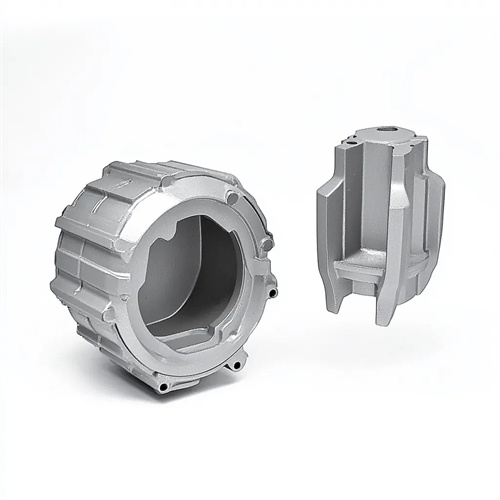

Casting mass and gate system volume are the fundamental data for calculating die-casting chamber capacity. Their sum constitutes the total amount of molten metal required for a single die-casting run. Casting mass can be calculated using 3D modeling software or by actual weighing. For complex castings, 3D modeling software (such as UG and Pro/E) can accurately calculate the volume, which is then multiplied by the alloy density to determine the mass, with an error within 2%. For simple castings, the volume can be measured using the water displacement method and then the mass calculated. The gate system, which includes the sprue, runner, ingate, and overflow channel, typically accounts for 10-30% of the casting volume, depending on the casting structure. Complex castings have a higher proportion of the gate system volume. For example, for valve body castings with multiple branches, the gate system volume can reach 25-30% of the casting volume, while simple flat plate castings require only 10-15%. When a die-casting plant produces an aluminum alloy gearbox housing, the mass of the casting is 3.5kg, the mass of the gate system is 1.0kg, and the total amount of molten metal required for a single time is 4.5kg. This data becomes the core basis for calculating the pressure chamber capacity.

Theoretical calculations of chamber capacity require consideration of the chamber’s fill rate. Typically, 70-85% of the chamber’s effective volume is considered the actual fill rate to avoid oxidation caused by excessive volume. The formula for calculating chamber effective volume is: effective volume = (π × chamber diameter² × chamber effective length) / 4, where the effective length is the distance from the chamber’s front end to the starting position of the injection punch. Multiplying the effective volume by the alloy density (e.g., aluminum alloy density is 2.7 g/cm³) yields the maximum chamber mass. Multiplying this by the fill rate (70-85%) yields the actual chamber mass. For example, the die chamber of a horizontal cold chamber die-casting machine has an 80mm diameter and an effective length of 300mm. Its effective volume is 3.14 × 4² × 30 = 1507.2cm³. The maximum molten metal mass is 1507.2 × 2.7 = 4070g. Based on an 80% fill rate, the actual molten metal mass it can accommodate is approximately 3256g. If the single molten metal demand is 4.5kg (4500g), the die chamber capacity is insufficient and a larger diameter or longer die chamber is required.

The selection of chamber capacity also needs to consider the injection stroke and the specific volume change of the molten metal to ensure that the molten metal completely fills the mold cavity during the injection process and avoids excessive waste. The injection stroke refers to the distance the injection punch moves from the starting position to the end position. This, together with the chamber diameter, determines the total chamber volume. When calculating the chamber capacity, it is important to ensure that the injection stroke can meet the molten metal filling requirements, while also leaving a 10-15% margin to avoid insufficient punch stroke. Molten metal undergoes specific volume change (volume contraction) under high pressure. The shrinkage rate varies between alloys, with aluminum alloy shrinkage rates of approximately 3-5% and zinc alloys of approximately 2-4%. This factor should be appropriately accounted for when calculating capacity. For example, for aluminum alloy castings, a 3% margin can be added to the theoretical molten metal volume. A company producing zinc alloy connectors failed to account for specific volume change, resulting in slightly less molten metal than required, resulting in a slight undercasting. Adding a 2% margin resolved the issue.

In actual production, the chamber capacity calculation needs to be adjusted based on the specific die-casting machine model and production efficiency. Chamber specifications (diameter and length) vary between different die-casting machine models, so a chamber that matches the required molten metal volume should be selected. If the existing chamber capacity is slightly smaller than required, a temporary solution can be achieved by shortening the starting position of the shot punch (increasing the effective length), but smooth punch movement must be ensured. If the capacity is too large, this can be addressed by reducing the amount of molten metal added each time (reducing the fill rate to 60-70%), but increased chamber cleaning is required to prevent scale accumulation. Furthermore, production efficiency also influences the capacity selection. For large-scale production, a chamber capacity slightly larger than required should be selected to reduce downtime caused by frequent molten metal additions. For small-batch production, the required capacity can be appropriately reduced to minimize metal waste. To improve production efficiency, an automotive parts manufacturer increased the chamber capacity from 4.5 kg (which just met the requirements) to 5.0 kg. This increased the interval between molten metal additions per die-casting run and increased the production line’s hourly capacity by 10%.

The accuracy of chamber capacity calculations requires verification and continuous optimization through trial production. During trial production, the molten metal filling, casting defects, and the residual volume of the chamber must be observed. If the chamber contains excessive residual volume (over 15%), the capacity is too large and a smaller chamber needs to be replaced. If the residual volume is too low and the casting is defective, the chamber capacity may be insufficient and the chamber needs to be increased. Furthermore, as subtle changes in casting quality occur during production (such as increased casting volume due to mold wear), the chamber capacity needs to be recalculated regularly, generally every 10,000 to 20,000 molds. One die-casting company has established a dynamic chamber capacity management mechanism. By regularly measuring the quality of castings and gate systems and adjusting the amount of molten metal added, the chamber fill rate is stabilized within the optimal range of 75-80%, increasing metal utilization by 5% and reducing the casting defect rate by 3%.